What Happens When Family Won't Care for Mentally Ill Person

What happens to our bodies afterward we die

(Image credit:

Getty Images

)

The breakdown of our bodies subsequently death can exist fascinating – if you dare to delve into the details. Mo Costandi investigates.

"Information technology might have a lilliputian scrap of strength to break this up," says mortician Holly Williams, lifting John'southward arm and gently bending it at the fingers, elbow and wrist. "Usually, the fresher a body is, the easier it is for me to work on."

Williams speaks softly and has a happy-get-lucky demeanour that belies the nature of her piece of work. Raised and now employed at a family-run funeral abode in north Texas, she has seen and handled dead bodies on an almost daily basis since childhood. Now 28 years old, she estimates that she has worked on something like 1,000 bodies.

Her work involves collecting recently deceased bodies from the Dallas–Fort Worth area and preparing them for their funeral.

"Most of the people we choice up die in nursing homes," says Williams, "simply sometimes nosotros get people who died of gunshot wounds or in a car wreck. We might get a call to pick upwards someone who died alone and wasn't found for days or weeks, and they'll already be decomposing, which makes my piece of work much harder."

John had been dead about four hours before his body was brought into the funeral abode. He had been relatively salubrious for most of his life. He had worked his whole life on the Texas oil fields, a job that kept him physically active and in pretty good shape. He had stopped smoking decades before and drank alcohol moderately. Then, one cold Jan morn, he suffered a massive middle attack at abode (patently triggered by other, unknown, complications), fell to the floor, and died almost immediately. He was only 57.

Now, John lay on Williams' metal table, his body wrapped in a white linen sheet, cold and stiff to the touch, his pare purplish-grey – tell-tale signs that the early stages of decomposition were well nether way.

Self-digestion

Far from being 'expressionless', a rotting corpse is teeming with life. A growing number of scientists view a rotting corpse every bit the cornerstone of a vast and complex ecosystem, which emerges soon after decease and flourishes and evolves every bit decomposition proceeds.

Decomposition begins several minutes after decease with a process called autolysis, or self-digestion. Presently after the centre stops chirapsia, cells become deprived of oxygen, and their acidity increases equally the toxic past-products of chemic reactions begin to accumulate within them. Enzymes start to digest cell membranes and then leak out equally the cells suspension downward. This commonly begins in the liver, which is rich in enzymes, and in the brain, which has high water content. Eventually, though, all other tissues and organs begin to break down in this way. Damaged blood cells begin to spill out of broken vessels and, aided by gravity, settle in the capillaries and small veins, discolouring the skin.

Body temperature also begins to drop, until information technology has acclimatised to its environs. Then, rigor mortis – "the stiffness of death" – sets in, starting in the eyelids, jaw and cervix muscles, before working its manner into the trunk and and then the limbs. In life, musculus cells contract and relax due to the actions of ii filamentous proteins (actin and myosin), which slide along each other. Afterward death, the cells are depleted of their energy source and the protein filaments become locked in identify. This causes the muscles to go rigid and locks the joints.

(Credit: Science Photo Library)

During these early on stages, the cadaveric ecosystem consists mostly of the leaner that live in and on the living homo body. Our bodies host huge numbers of bacteria; every one of the torso's surfaces and corners provides a habitat for a specialised microbial community. By far the largest of these communities resides in the gut, which is dwelling house to trillions of bacteria of hundreds or mayhap thousands of different species.

The gut microbiome is i of the hottest research topics in biological science; it'due south been linked to roles in human being health and a plethora of weather condition and diseases, from autism and low to irritable bowel syndrome and obesity. Only we still know little about these microbial passengers while we are alive. Nosotros know even less near what happens to them when we die.

Immune shutdown

In Baronial 2014, forensic scientist Gulnaz Javan of Alabama Land University in Montgomery and her colleagues published the very first study of what they have called the thanatomicrobiome (from thanatos, the Greek word for 'death').

"Many of our samples come from criminal cases," says Javan. "Someone dies by suicide, homicide, drug overdose or traffic blow, and I collect tissue samples from the body. In that location are ethical bug [considering] we need consent."

Nearly internal organs are devoid of microbes when we are live. Soon afterwards expiry, nevertheless, the immune system stops working, leaving them to spread throughout the body freely. This usually begins in the gut, at the junction between the small-scale and large intestines. Left unchecked, our gut bacteria begin to assimilate the intestines – so the surrounding tissues – from the inside out, using the chemical cocktail that leaks out of damaged cells as a food source. Then they invade the capillaries of the digestive system and lymph nodes, spreading first to the liver and spleen, then into the heart and encephalon.

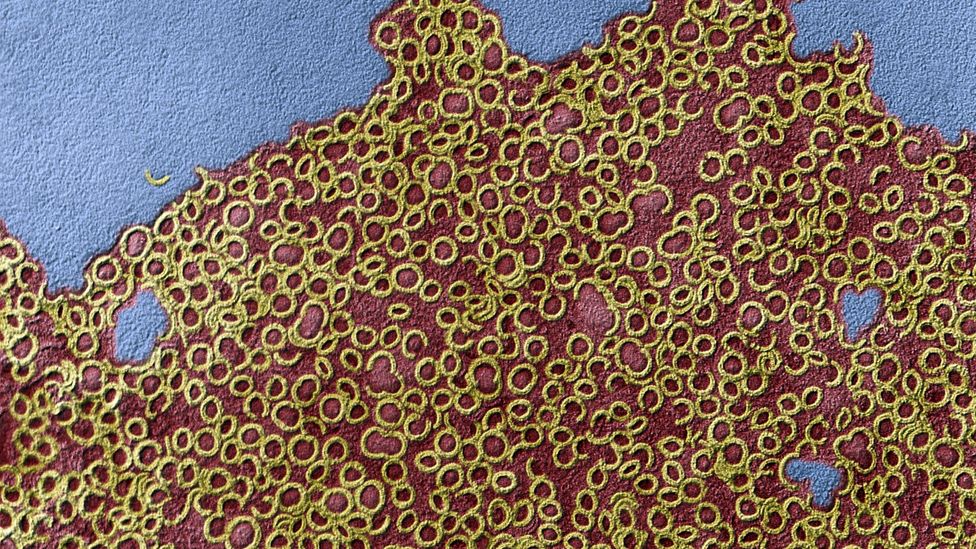

Leaner convert the haemoglobin in blood into sulfhaemoglobin (Credit: Science Photo Library)

Javan and her team took samples of liver, spleen, brain, heart and blood from 11 cadavers, at between xx and 240 hours after death. They used two different state-of-the-fine art DNA sequencing technologies, combined with bioinformatics, to analyse and compare the bacterial content of each sample.

The samples taken from dissimilar organs in the aforementioned cadaver were very similar to each other but very different from those taken from the same organs in the other bodies. This may exist due partly to differences in the limerick of the microbiome of each cadaver, or it might be caused by differences in the time elapsed since death. An before study of decomposing mice revealed that although the microbiome changes dramatically later on expiry, information technology does so in a consistent and measurable way. The researchers were able to estimate time of expiry to within three days of a most two-month period.

Leaner checklist

Javan's study suggests that this 'microbial clock' may be ticking within the decomposing human body, as well. It showed that the bacteria reached the liver well-nigh 20 hours subsequently death and that information technology took them at least 58 hours to spread to all the organs from which samples were taken. Thus, later nosotros die, our leaner may spread through the body in a systematic way, and the timing with which they infiltrate outset one internal organ and and so some other may provide a new style of estimating the amount of time that has elapsed since death.

"Subsequently decease the limerick of the bacteria changes," says Javan. "They move into the heart, the brain so the reproductive organs last." In 2014, Javan and her colleagues secured a $200,000 (£131,360) grant from the National Science Foundation to investigate further. "Nosotros will practice next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics to see which organ is best for estimating [time of death] – that's still unclear," she says.

One affair that does seem clear, however, is that a different limerick of bacteria is associated with different stages of decomposition.

The microbiome of leaner changes with each hour after death (Credit: Getty Images)

Just what does this process actually look like?

Scattered among the pine trees in Huntsville, Texas, lie around half a dozen human cadavers in various stages of disuse. The two most recently placed bodies are spread-eagled nigh the centre of the small enclosure with much of their loose, grey-blueish mottled skin nonetheless intact, their ribcages and pelvic bones visible between slowly putrefying flesh. A few metres abroad lies another, fully skeletonised, with its black, hardened skin clinging to the bones, equally if information technology were wearing a shiny latex accommodate and skullcap. Further nevertheless, beyond other skeletal remains scattered by vultures, lies a third body within a wood and wire cage. It is nearing the end of the death cycle, partly mummified. Several large, dark-brown mushrooms grow from where an abdomen in one case was.

Natural decay

For most of us the sight of a rotting corpse is at best unsettling and at worst repulsive and frightening, the stuff of nightmares. Merely this is everyday for the folks at the Southeast Texas Applied Forensic Science Facility. Opened in 2009, the facility is located inside a 247-acre area of national forest owned by Sam Houston State Academy (SHSU). Within it, a nine-acre plot of densely wooded land has been sealed off from the wider area and further subdivided, by ten-foot-high green wire fences topped with barbed wire.

In tardily 2011, SHSU researchers Sibyl Bucheli and Aaron Lynne and their colleagues placed two fresh cadavers here, and left them to decay nether natural conditions.

Once self-digestion is under style and leaner have started to escape from the alimentary canal, putrefaction begins. This is molecular death – the breakdown of soft tissues even further, into gases, liquids and salts. It is already under way at the earlier stages of decomposition but really gets going when anaerobic leaner arrive on the act.

Every dead torso is likely to accept its own unique microbial signature (Credit: Science Photo Library)

Putrefaction is associated with a marked shift from aerobic bacterial species, which require oxygen to grow, to anaerobic ones, which do not. These then feed on the torso'due south tissues, fermenting the sugars in them to produce gaseous by-products such as methyl hydride, hydrogen sulphide and ammonia, which accumulate within the body, inflating (or 'bloating') the abdomen and sometimes other trunk parts.

This causes further discolouration of the body. As damaged claret cells proceed to leak from disintegrating vessels, anaerobic bacteria convert haemoglobin molecules, which once carried oxygen effectually the body, into sulfhaemoglobin. The presence of this molecule in settled blood gives skin the marbled, green-blackness advent characteristic of a body undergoing active decomposition.

Specialised habitat

As the gas pressure continues to build up inside the trunk, information technology causes blisters to announced all over the peel surface. This is followed by loosening, and and so 'slippage', of large sheets of skin, which remain barely attached to the deteriorating frame underneath. Eventually, the gases and liquefied tissues purge from the body, usually leaking from the anus and other orifices and often also leaking from ripped skin in other parts of the body. Sometimes, the pressure is so great that the abdomen bursts open.

Bloating is ofttimes used as a marking for the transition between early on and later stages of decomposition, and another contempo study shows that this transition is characterised past a distinct shift in the composition of cadaveric bacteria.

Bucheli and Lynne took samples of leaner from various parts of the bodies at the showtime and the finish of the bloat phase. They then extracted bacterial Dna from the samples and sequenced it.

Flies lay eggs on a cadaver in the hours after death, either in orifices or open wounds (Credit: Science Photo Library)

Equally an entomologist, Bucheli is mainly interested in the insects that colonise cadavers. She regards a cadaver every bit a specialised habitat for various necrophagous (or 'dead-eating') insect species, some of which see out their entire life bike in, on and effectually the body.

When a decomposing body starts to purge, it becomes fully exposed to its surround. At this phase, the cadaveric ecosystem really comes into its own: a 'hub' for microbes, insects and scavengers.

Maggot cycle

Two species closely linked with decomposition are blowflies and mankind flies (and their larvae). Cadavers give off a foul, sickly-sugariness odour, made up of a circuitous cocktail of volatile compounds which changes as decomposition progresses. Blowflies detect the smell using specialised receptors on their antennae, then land on the cadaver and lay their eggs in orifices and open wounds.

Each fly deposits effectually 250 eggs that hatch inside 24 hours, giving rise to small-scale showtime-stage maggots. These feed on the rotting flesh and so moult into larger maggots, which feed for several hours before moulting once again. Afterwards feeding some more, these nonetheless larger, and at present fattened, maggots wriggle away from the trunk. They and so pupate and transform into adult flies, and the cycle repeats until there's zippo left for them to feed on.

Wriggling maggots generate an enormous amount of heat inside the torso (Credit: Scientific discipline Photo Library)

Under the right weather condition, an actively decaying body will have large numbers of phase-3 maggots feeding on information technology. This 'maggot mass' generates a lot of estrus, raising the inside temperature by more than 10C (18F). Similar penguins huddling in the S Pole, individual maggots inside the mass are constantly on the move. But whereas penguins huddle to keep warm, maggots in the mass motion around to stay cool.

"Information technology'southward a double-edged sword," Bucheli explains, surrounded by large toy insects and a collection of Monster High dolls in her SHSU office. "If you're e'er at the edge, you might get eaten by a bird, and if y'all're always in the centre, y'all might become cooked. So they're constantly moving from the heart to the edges and back."

The presence of flies attracts predators such every bit pare beetles, mites, ants, wasps and spiders, which then feed on the flies' eggs and larvae. Vultures and other scavengers, equally well equally other large meat-eating animals, may as well descend upon the body.

Unique repertoire

In the absence of scavengers, though, the maggots are responsible for removal of the soft tissues. As Carl Linnaeus (who devised the system past which scientists proper noun species) noted in 1767, "iii flies could consume a equus caballus cadaver as chop-chop as a lion". Third-stage maggots will move away from a cadaver in big numbers, often following the aforementioned route. Their activity is so rigorous that their migration paths may be seen after decomposition is finished, as deep furrows in the soil emanating from the cadaver.

Every species that visits a cadaver has a unique repertoire of gut microbes, and unlike types of soil are likely to harbour distinct bacterial communities – the composition of which is probably determined past factors such as temperature, moisture, and the soil type and texture.

(Credit: Science Photo Library)

All these microbes mingle and mix within the cadaveric ecosystem. Flies that country on the cadaver will not only eolith their eggs on it, but will also take up some of the bacteria they find at that place and leave some of their ain. And the liquefied tissues seeping out of the body allow the substitution of bacteria between the cadaver and the soil beneath.

When they have samples from cadavers, Bucheli and Lynne detect bacteria originating from the skin on the body and from the flies and scavengers that visit it, every bit well every bit from soil. "When a torso purges, the gut bacteria start to come out, and we run into a greater proportion of them exterior the torso," says Lynne.

Thus, every dead trunk is likely to accept a unique microbiological signature, and this signature may change with time according to the verbal conditions of the death scene. A improve understanding of the limerick of these bacterial communities, the relationships betwixt them and how they influence each other equally decomposition proceeds could one day assist forensics teams learn more most where, when and how a person died.

Pieces of the puzzle

For instance, detecting Deoxyribonucleic acid sequences known to be unique to a particular organism or soil type in a cadaver could help crime scene investigators link the trunk of a murder victim to a item geographical location or narrow downwardly their search for clues even further, mayhap to a specific field within a given surface area.

"There have been several court cases where forensic entomology has really stood up and provided important pieces of the puzzle," says Bucheli, adding that she hopes bacteria might provide additional information and could become some other tool to refine time-of-death estimates. "I hope that in about five years we can start using bacterial data in trials," she says.

To this end, researchers are busy cataloguing the bacterial species in and on the human being body, and studying how bacterial populations differ between individuals. "I would love to accept a dataset from life to death," says Bucheli. "I would dearest to run into a donor who'd allow me accept bacterial samples while they're alive, through their death procedure and while they decompose."

Drones could be used to find buried bodies by analysing soil (Credit: Getty Images)

"We're looking at the purging fluid that comes out of decomposing bodies," says Daniel Wescott, director of the Forensic Anthropology Centre at Texas State University in San Marcos.

Wescott, an anthropologist specialising in skull construction, is using a micro-CT scanner to analyse the microscopic structure of the bones brought back from the body subcontract. He also collaborates with entomologists and microbiologists – including Javan, who has been busy analysing samples of cadaver soil collected from the San Marcos facility – as well equally figurer engineers and a pilot, who operate a drone that takes aerial photographs of the facility.

"I was reading an article about drones flying over crop fields, looking at which ones would exist best to plant in," he says. "They were looking at well-nigh-infrared, and organically rich soils were a darker colour than the others. I thought if they tin can do that, then perchance we can selection up these trivial circles."

Rich soil

Those "little circles" are cadaver decomposition islands. A decomposing body significantly alters the chemistry of the soil beneath it, causing changes that may persist for years. Purging – the seeping of broken-down materials out of what'due south left of the body – releases nutrients into the underlying soil, and maggot migration transfers much of the energy in a torso to the wider environment.

Eventually, the whole procedure creates a 'cadaver decomposition island', a highly concentrated area of organically rich soil. As well every bit releasing nutrients into the wider ecosystem, this attracts other organic materials, such every bit expressionless insects and faecal matter from larger animals.

According to 1 approximate, an average human body consists of fifty–75% water, and every kilogram of dry out body mass eventually releases 32g of nitrogen, 10g of phosphorous, 4g of potassium and 1g of magnesium into the soil. Initially, it kills off some of the underlying and surrounding vegetation, possibly considering of nitrogen toxicity or because of antibiotics found in the body, which are secreted by insect larvae as they feed on the mankind. Ultimately, though, decomposition is beneficial for the surrounding ecosystem.

A dead body's minerals continue to leach into soil months after death (Credit: Getty Images)

The microbial biomass within the cadaver decomposition island is greater than in other nearby areas. Nematode worms, associated with decay and drawn to the seeping nutrients, become more abundant, and plant life becomes more diverse. Further enquiry into how decomposing bodies modify the ecology of their surroundings may provide a new style of finding murder victims whose bodies accept been buried in shallow graves.

Grave soil analysis may besides provide another possible way of estimating time of death. A 2008 report of the biochemical changes that have place in a cadaver decomposition isle showed that the soil concentration of lipid-phosphorous leaking from a cadaver peaks at effectually 40 days later decease, whereas those of nitrogen and extractable phosphorous acme at 72 and 100 days, respectively. With a more detailed understanding of these processes, analyses of grave soil biochemistry could one mean solar day help forensic researchers to estimate how long ago a body was placed in a hidden grave.

This is an edited version of an article originally published by Mosaic, and is reproduced under a Artistic Commons licence. For more almost the issues effectually this story, visit Mosaic's website here.

Share this story on Facebook , Google+ or Twitter .

Source: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20150508-what-happens-after-we-die

0 Response to "What Happens When Family Won't Care for Mentally Ill Person"

Post a Comment